Driven by an indomitable spirit: UM honorary doctor Prof Ze Zhang

‘The properties of materials are always hidden in their crystal structure,’ says Ze Zhang, honorary doctor of the University of Macau (UM). For decades, his research has been devoted to uncovering this hidden order through crystallography and advanced materials characterisation. From a childhood shaped by rural hardship to a career forged amid China’s rapidly evolving scientific landscape, Prof Zhang has devoted his life to bridging the macroscopic and microscopic worlds. His pioneering work in electron microscopy has played a central role in advancing the field and deepening contemporary understanding of material behaviour.

Bridging scales: from giants to Lilliput

‘My focus on crystal microstructure research began when I studied metal physics at Jilin University. I have always believed that exploring the microscopic structure of matter is the key to unlocking the fundamental properties of materials—whether electrical, optical, magnetic, or mechanical,’ Prof Zhang recalls. From the outset of his academic journey, he was drawn to the hidden structures of matter and their decisive influence on material performance. Yet in his early years of research, an invisible barrier seemed to separate microscopic structures from macroscopic behaviour. Overcoming this divide would become a long‑standing ambition in materials science—and a central challenge in his own work.

‘When I was pursuing my doctoral degree, a professor who studied fracture once asked us: “As researchers in microstructural analysis, you can see atoms—but can you see how materials fracture at the atomic level?”’ Prof Zhang recalls. At the time, the question felt almost impossible to answer. ‘Fracture phenomena and atoms differ by six or seven orders of magnitude—like the difference between a galaxy and a grain of dust. How could we possibly find a connection?’ Yet the question went to the heart of the discipline. The ultimate goal of materials research is performance, and performance is rooted in structure. Bridging macroscopic behaviour and microscopic mechanisms was not merely a challenge—it was the only way forward.

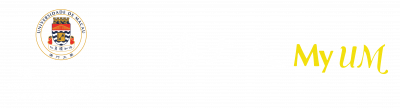

Prof Zhang engages with UM postgraduate students

Within the scientific community, this problem is often described as working between the ‘land of giants’ and the ‘land of Lilliput’. Recreating the mechanical and thermal conditions of stretching, bending, and heating at the atomic scale is, as Prof Zhang puts it, ‘like recreating the world of giants in a land of little people’. Simply scaling everything down is not enough; the underlying processes must still function. Pulling a rope is easy, he notes, but grasping a single hair is far more difficult. When the object becomes even thinner, there may be nothing left to hold on to.

Such research is never easy. For many years, it was further constrained by dependence on imported high‑end electron microscopes, shortages of supporting tools and components, and gaps in technical expertise. To overcome these limitations, Prof Zhang spearheaded an application for a national major scientific instrument development project. His goal was to clarify how structural evolution under extreme conditions determines material performance. The experimental parameters he proposed—temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius and stresses above 100 megapascals—mirror those experienced in the most critical regions of turbine blades in aero‑engines.

This effort spanned more than a decade, including five years of systematic research and documentation, as well as extensive preliminary preparation and subsequent refinement. Ultimately, Prof Zhang led his team to achieve two major national scientific and technological breakthroughs: the development of an in situ characterisation system with atomic lattice resolution for high‑temperature mechanics studies, and a complementary in situ system capable of nanoscale resolution for high‑temperature mechanics.

Turning research results into practical applications

What is moving is not only the perseverance behind Prof Zhang’s scientific achievements, but also his determination to carry them beyond the laboratory and into real‑world use. Although the national research project he led did not require industrialisation, he insisted on transforming the outcomes into practical technologies. This conviction is rooted in a strong sense of responsibility and shaped by his early life experiences. From the age of sixteen, Prof Zhang spent eight years as a sent‑down youth in Inner Mongolia—an experience that gave him a profound understanding of hardship and the value of work. ‘The national project funding amounted to tens of millions of yuan, and every cent carried trust,’ he says. ‘I felt a responsibility to create something genuinely useful in return.’

The challenges of industrialisation, he soon discovered, far exceeded those of scientific research itself. As Prof Zhang explains succinctly, ‘In scientific instrument research, a single successful experiment is a victory; in industrialisation, even one failure out of a hundred experiments is still a failure.’ The pressure to avoid mistakes was immense, yet he never doubted the importance of the effort. ‘The true meaning of scientific research lies in its ability to become a universally applicable tool—one that enables more researchers to solve problems and conduct experiments more efficiently,’ he says.

Prof Zhang discusses the microstructure of advanced materials at the UM honoris causa Lecture

To ensure that his research could be transformed into reliable, usable technologies, Prof Zhang invested his own funds and, with the support of venture capital, acquired the relevant patents and established a company. Together with his team, he developed two force-thermal‑coupled operating systems based on atomic‑ and nanoscale electron microscopes. Unlike traditional transmission and scanning electron microscopes, which function solely as ‘eyes’, these systems also provide the operational capability of a ‘hand’ at atomic and nanoscale resolution, enabling true ‘hand–eye’ coordination during experiments. Today, these technologies have been successfully commercialised, generating annual sales of 10 to 30 million yuan. The atomic‑resolution electron microscope has even been exported to Germany—the birthplace of the electron microscope—as well as to Denmark, a global leader in the field.

More importantly, Prof Zhang notes, ‘we are no longer held back by technology.’ With what he calls a ‘diamond drill’, his team can support national engineering projects and research laboratories in tackling the most demanding challenges. Researchers can now directly observe how the performance of critical components evolves under different stresses and temperatures. Even students conducting routine experiments have benefited. ‘In the past, damage to a microscope could cost hundreds of thousands of yuan,’ he recalls. ‘What was even more frustrating was the months‑long wait for repairs or replacements, during which experiments came to a complete standstill.’

Cultivating ability, nurturing imagination

Returning to UM to receive his honorary doctorate, Prof Zhang was visibly moved. Having served for many years as director of the Academic Committee of the UM Institute of Applied Physics and Materials Engineering, he has remained deeply engaged with the university’s academic development and played a leading role in establishing the Master of Science programme in Innovative Materials. Our interview took place in the institute’s exhibition hall. Before it began, Prof Zhang slowed his pace to examine each display carefully, studying the exhibits in detail and frequently turning to ask UM staff about their application prospects and development potential—an expression of his sustained curiosity and commitment to education.

Prof Zhang receives a Doctor of Science honoris causa from UM

‘The mission of universities is not to train “professional robots”, but to cultivate thinkers,’ Prof Zhang observes. In his view, universities exist to explore the unknown, and postgraduate education represents the most dynamic period of knowledge creation. ‘Nearly all of the world’s most innovative research is conceived at the doctoral level,’ he emphasises. This belief was a key motivation behind his involvement in establishing the Master of Science programme in Innovative Materials. While graduates may pursue careers that differ from their original majors, what ultimately matters is their ability to identify and solve problems. The master’s stage, he explains, should focus on developing independent research skills, while doctoral training requires sharpening the capacity to confront challenges autonomously and to lead teams. ‘These abilities cannot be measured by examination scores; they must be developed through practice.’

In the age of artificial intelligence, Prof Zhang places particular emphasis on hands‑on skills, which he regards as the cornerstone of scientific research. Influenced by Galileo’s experimental philosophy, he underscores the central role of experimentation in the pursuit of scientific truth. ‘Experimentation is the criterion for testing truth. Only through experimentation can the virtual and the theoretical be transformed into reality,’ he says. He notes that many students today learn primarily from images of metallographic experiments and memorise definitions from textbooks. Yet when they conduct experiments themselves—stretching metal under an electron microscope and observing structural changes firsthand—the depth and completeness of their understanding are fundamentally different from simply viewing images. Prof Zhang strongly endorses UM’s efforts to create an environment in which students can participate directly in experimental research. ‘This is the key to cultivating outstanding research talent,’ he notes. ‘Only by allowing students to explore through practice and gain insight through experience can they truly consolidate their academic foundations.’

At the core of Prof Zhang’s educational philosophy, and of his support for the master’s programme in innovative materials, is the conviction that disciplinary boundaries must be broken down. ‘Today’s problems are all “hybrids”—intertwined and interdependent,’ he explains. Integrated circuit research, for example, requires expertise in both design and manufacturing, while perovskite research demands knowledge spanning physics and chemistry. He therefore encourages students to take courses across disciplines and to interact with peers from different academic backgrounds, applying interdisciplinary thinking to complex problems. At the same time, he advocates a holistic approach to education, emphasising that the integration of humanistic imagination with scientific logic can spark unexpected insights. ‘I even encourage students to view atomic‑scale images under the microscope as vast landscapes and to write poems or essays about them,’ he says. ‘Curiosity and imagination are the wellspring of scientific research.’

UM Rector Yonghua Song presents Prof Zhang with a letter of appointment as director of the Academic Committee of the UM Institute of Applied Physics and Materials Engineering

Driven by curiosity, sustained by perseverance

When asked what has fuelled his unwavering dedication to scientific research, Prof Zhang answers without hesitation: ‘First, curiosity; second, an indomitable spirit.’ Quoting a line from the Chinese film Pegasus, he smiles with youthful vigour: ‘It’s not about having to win—I simply don’t want to lose. That probably captures the spirit of our generation.’ From learning the English alphabet at the age of 24 to, now in his seventies, delivering fluent lectures in English at the UM Doctor honoris causa Lecture on in situ microstructural research; from a sent‑down youth in Inner Mongolia to a leading figure in materials science—Prof Zhang’s life itself is a testament to perseverance and an enduring refusal to yield. This resilience continues to underpin the many roles he balances today.

When navigating the demands of scientific research, industrialisation, and talent cultivation, Prof Zhang’s guiding principle is to ‘focus on the big picture and let go of the small details.’ As he explains, ‘A person’s energy is like sand in the hand—the tighter you grasp it, the more it slips through your fingers. Let capable people take charge of important tasks, and I will serve as the “bridge” connecting all parties, transforming microstructural research from something no one used into something everyone needs. That sense of accomplishment is something money cannot buy.’

Drawing on decades of experience in both research and industry, Prof Zhang is also eager to share insights with enterprises. One principle he consistently advocates is the establishment of a Chief Technology Officer. ‘Engineers are the “legs”—they are skilled at solving practical problems—while scientists are the “brain”, able to perceive future directions,’ he explains. ‘Each has its limitations, but when vision and execution work together, they complement one another. Especially when industry enters uncharted territory with no precedents to follow, this synergy is essential for choosing the right direction and moving forward with confidence.’

Prof Zhang attends a meeting of the Academic Committee of the UM Institute of Applied Physics and Materials Engineering

This indomitable spirit and deep passion for science also shape Prof Zhang’s expectations for the next generation of scholars. ‘Science has no boundaries,’ he says. ‘Research centred on X‑rays alone has led to at least 25 Nobel Prizes—from their discovery, to the development of chromatography, to cross‑disciplinary applications in genetic research. Every step represents a creative breakthrough in human understanding.’ This was also the message Prof Zhang shared two years ago in his talk ‘Veritas, Innovation, Civilization & Progress’ at UM. He hopes that more young people will step into the world of science. ‘Don’t give up. Don’t complain about being born at the wrong time. This era is full of opportunities. Knowledge has no boundaries—anyone willing to delve deeply, imagine boldly, and challenge themselves courageously will find their rewards.’

Though atoms are tiny, they reveal the universe; though structures are complex, their underlying principles can be traced. From seeing atoms clearly to bridging the micro and the macro, from the laboratory to industrial application, Prof Zhang has not only uncovered the mechanisms underlying material performance, but also embodied the responsibility and commitment of a scientist. As he often reminds others, scientific exploration has no endpoint—like the motion of atoms themselves, it never ceases. As long as one remains curious and perseveres, they can chart their own path and discover a universe of possibilities within their chosen field.

Profile of Prof Ze Zhang

Prof Ze Zhang is an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and a professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at Zhejiang University, where he also serves as chair of the Advisory Committee of the Academic Committee. A leading figure in international quasicrystal research, he has devoted many years to the study of the electronic microstructure of advanced materials. Prof Zhang’s work has systematically addressed key scientific challenges in quasicrystals and low‑dimensional nanomaterials, resulting in a series of innovative research contributions that are widely recognised at the forefront of the field.

Chinese Text: Gigi Fan

English Translation: Bess Che

Photo: Jack Ho

Video: Hasen Cai, Reporter Leontius Liu, Reporter Trainee Zoey Xiao & Katy Chen

Source: My UM Issue 150