A lifelong inquiry: Thomas Sargent, Nobel laureate and UM honorary doctor

‘If I had believed that the results of my IQ test would define my life, I wouldn’t have become who I am today,’ says Thomas J. Sargent, a Nobel laureate in Economic Sciences who recently received a Doctor of Business Administration honoris causa from the University of Macau (UM). Although his teachers once questioned his future because he learned more slowly than his peers, Prof Sargent never lost faith in himself. Through relentless effort and intellectual curiosity, he went on to pioneer the ‘rational expectations revolution’, reshaping modern economics and ultimately earning the Nobel Prize. Yet what makes him especially admirable is not only his groundbreaking achievements, but also his humility. Despite numerous honours and accolades, he continues to describe himself as a ‘lifelong student’. Now over eighty years old, his journey demonstrates that true wisdom arises not merely from innate brilliance, but from perseverance, curiosity, and an enduring commitment to learning.

A Nobel laureate with a taste for leisurely walks

Our interview with Prof Sargent takes place at the Faculty of Business Administration (FBA) on a warm winter afternoon. Instead of taking the arranged car ride to the venue, he chooses to walk, eager to explore the roughly half‑kilometre route on foot. ‘I travelled from afar to UM,’ he says with a smile. ‘I want to take a good look around.’ And so, beneath the gentle sunshine, we begin a leisurely stroll with the Nobel laureate.

Prof Sargent moves with a steady, assured gait along the Central Avenue on campus. Tall and composed, he wears a neat, old‑fashioned suit that accentuates his robust frame. His silvery‑grey hair, meticulously combed, catches the afternoon light, gleaming like fresh snow. Walking beside him is Yu Jun, dean of FBA, and the two continue a lunchtime discussion with evident enthusiasm, their conversation unfolding naturally as they move.

Prof Sargent and Prof Yu Jun engage in an animated discussion on the Central Avenue on UM campus

Ahead of the meeting, Prof Sargent had carefully studied Prof Yu’s academic work. Prof Yu’s analyses of statistical inference—drawing on both the frequentist and Bayesian traditions—offered Prof Sargent fresh perspectives, some of which he has begun to weave into his own interdisciplinary research spanning macroeconomics, monetary policy, and economic history. Yet scholarship on the page differs from dialogue in person. As the two scholars walk, ideas pass easily between them, their exchange moving beyond written words to become more immediate, animated, and profound.

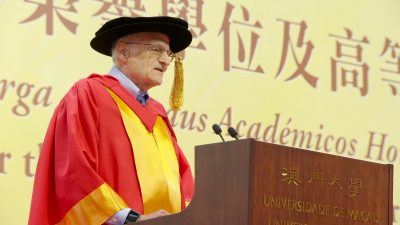

This conversation in motion reflects Prof Sargent’s decades‑long commitment to learning. Neither age nor honour has diminished his curiosity or eagerness for intellectual exchange. His pioneering contributions to empirical research on macroeconomic cause and effect earned him the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2011. In November 2025, he received a Doctor of Business Administration honoris causa from UM. In his acceptance speech, Prof Sargent emphasised that he accepted the honour not as a finished scholar, but as a grateful student. Long regarding himself less as a teacher than a learner—a persistent importer of ideas—his humility and sincerity left a lasting impression on the faculty and students in attendance.

From a slow leaner to a Nobel laureate

In the public imagination, Prof Sargent is often regarded as a genius, his name inseparable from the prestige of the Nobel Prize. Macroeconomics, after all, is a demanding and highly abstract field, and those who reach its highest ranks are commonly assumed to possess extraordinary intellectual gifts.

Yet Prof Sargent’s own story tells a very different tale.

‘When I was in high school, my teachers had my IQ test,’ Prof Sargent recalls calmly. ‘They didn’t place me with the advanced students. They even told me I couldn’t go to the college I wanted to attend.’ He pauses briefly, his gaze steady. ‘It was because I learned slowly and had some learning disabilities. But I was persistent, and I was always curious about the world. I believe that persistence and curiosity have been my most valuable assets throughout my academic journey.’

Prof Sargent not only gained admission to the University of California, Berkeley—his dream school, an outcome his teachers once doubted—but also graduated with top honours, earning a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1964. He went on to receive his PhD in economics from Harvard University in 1968. Over the following decades, his academic career led him through many of the world’s leading institutions, including New York University, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Minnesota, the University of Chicago, Stanford University, and Princeton University.

Prof Sargent receives a Doctor of Business Administration honoris causa from UM

Despite these achievements, Prof Sargent remains deeply committed to the enduring value of foundational scholarship. ‘If you look at the books on my shelf,’ he says, ‘the ones I studied in college that have the longest half-life are the classics in fundamental subjects.’ He often points to a book on time-series statistics as an example. ‘If you open it, every page is filled with my dense markings and notes. Even when I reread it today, the material is still deeply ingrained in my mind. It is this solid foundation that enables researchers to explore problems in depth.’

In Prof Sargent’s view, mastery of such fundamentals can empower even an average student to engage creatively with complex problems. ‘A lot of the recreative stuff is very marginal,’ he observes. ‘It is tweaking existing frameworks—seeing how a robust theory might work a little better. Scientific progress often depends on the accumulation of these incremental improvements.’

Prof Sargent delivers a speech at UM’s Ceremony for the Conferment of Honorary Degrees and Higher Degrees

Unchanging principles in a changing world

This emphasis on foundational knowledge remains valid—and perhaps gains even more importance—in a world shaped by rapidly evolving technology. In today’s information‑saturated age, Prof Sargent believes that sustained engagement with classic works and a firm grasp of basic principles are not outdated practices, but enduring necessities. ‘Some fundamental laws that govern the world do not change with technological advancement,’ he says calmly.

As an example, Prof Sargent points to The Blank Slate by cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker. He notes that Chapter 13 addresses a question that remains relevant today: how best to understand the world amid rapid social and technological change. ‘Pinker argues that education should prioritise three fundamental areas,’ Prof Sargent explains. ‘I would add a fourth. Together, these fields form the core principles for understanding how the world works.’

Prof Sargent interacts with UM doctoral students

The four fields he identifies are statistics, biology, economics, and—importantly, he adds—physics. Statistics teaches how to reason about probability distributions and uncertainty through data; biology reveals the mechanisms of adaptation and evolution in complex systems; economics analyses logic, incentives, and the allocation of scarce resources; and physics provides the most fundamental framework for understanding the material world.

‘You might wonder why one should bother learning these subjects in the age of artificial intelligence (AI),’ Prof Sargent continues. ‘But it is precisely these fields that provide the tools AI researchers use to develop systems such as DeepSeek.’ In his view, mastery of these disciplines is essential for understanding how AI functions beneath the surface—and for meaningfully contributing to its improvement. ‘The people who build systems like DeepSeek are typically experts in one or more of these areas.’

Prof Sargent extends this argument beyond science and technology, emphasising the universal value of fundamentals across disciplines. ‘Whatever you do—dance, ballet, singing, or music composition—the first thing you must learn is the basics: fundamental movements, structures, and principles,’ he says. Once those principles are mastered, he explains, it becomes possible to adapt and acquire new techniques at remarkable speed, even as the external world continues to change. Complex real‑world problems—whether involving decision‑making under uncertainty, resource allocation, or market dynamics—often require the combined application of ideas drawn from these foundational fields.

‘If you don’t understand the underlying principles, technology becomes like magic. You can use it, but you don’t really know how it works,’ Prof Sargent observes. ‘By contrast, understanding the “why” behind the tools grants the ability not only to apply them, but to improve upon them. Those who grasp the underlying mechanisms are the ones who know how to move things forward.’

‘When people say that things are completely different now than when I was young, they are right—in one sense,’ Prof Sargent adds thoughtfully. ‘But in another sense, the fundamental principles that govern the world remain unchanged. This is not only the core of learning; it is also the foundation for facing whatever changes lie ahead.’

When a rising tide fails to lift all boats

Over the course of his academic career, Prof Sargent has witnessed several major paradigm shifts in macroeconomics. From the dominance of Keynesianism, through the rise of the rational expectations revolution, to the current emphasis on micro‑level data, causal inference, and empirical rigour, the field has undergone profound transformations. Prof Sargent and fellow Nobel laureate Robert Lucas Jr. belong to the same academic generation, sharing a common theoretical language and analytical toolkit. Yet on one crucial issue, their paths diverged.

Lucas is best known for the Lucas Critique, which argues that historical data alone cannot reliably predict the effects of new economic policies. Building on this insight, he famously calculated that even if economic fluctuations were entirely eliminated, the resulting welfare gains would amount to less than one per cent of national income. From this perspective, economic stability and income distribution could be treated as largely separate policy concerns. This conclusion, however, rests on a critical assumption: the representative agent model, in which all households are treated as an ‘average’ individual. It was precisely this assumption that Prof Sargent found problematic, as it conflicted with his long‑standing attention to differences in lived economic realities.

‘Whose cost is the so‑called welfare cost of economic fluctuations?’ Prof Sargent asks. ‘Does a recession mean the same thing to a Wall Street banker as it does to an auto worker in Detroit?’ These questions led him towards a pivotal shift in modern macroeconomic thinking—from representative agent models to heterogeneous agent frameworks. To test the real‑world implications of Lucas’s argument, Prof Sargent turned to detailed household‑level data, tracking long‑term economic outcomes across income groups. The evidence was unmistakable: the effects of economic shocks are highly unequal and often persist for many years.

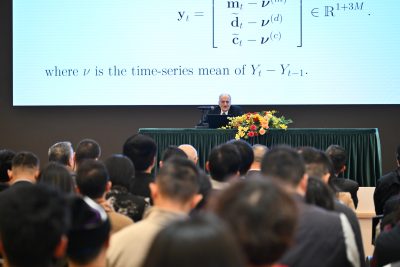

Prof Sargent discusses the quantification of redistribution and insurance using US household data at the UM Doctor honoris causa Lecture

The 2008 global financial crisis offers a stark illustration. Prof Sargent’s research shows that households in the bottom ten per cent of income distribution suffered devastating losses and, even many years later, had yet to fully recover. Middle‑income households experienced less severe damage, but their recovery proved slow and fragile. By contrast, the wealthiest ten per cent rebounded quickly and continued to accumulate wealth. Economic fluctuations, he argues, are therefore not simply collective rises and falls. They function instead as powerful—and often unfair—distribution mechanisms, deepening disadvantage for some while reinforcing privilege for others. As Prof Sargent puts it, ‘When designing stability policies, we cannot pretend they are unrelated to distribution. The process of “making the pie bigger” itself determines how the pie is divided.’

These ideas came together with striking clarity during Prof Sargent’s Doctor honoris causa Lecture at UM. In just one hour, and without notes or rhetorical flourish, he synthesised Lucas’s foundational insights, the limitations of traditional models, and the latest findings from heterogeneity research into a coherent and compelling framework. Guided by concise charts and rigorous derivations, he navigated decades of theoretical debate and empirical evidence, rendering complex ideas both accessible and precise. His command of the material—and his ability to illuminate its real‑world implications—left a deep impression on the scholars in attendance.

As long as the questions continue

Throughout his academic career, Prof Sargent has been guided by two enduring pursuits: understanding the world and understanding himself. When speaking to students about career choices, he often invokes the idea of ‘experience as a commodity’, arguing that only through direct engagement can one discover what one truly enjoys and what one is genuinely good at. Learning, he tells them, is less about arriving at predetermined answers than about exploration. ‘You may find yourself studying something you are not immediately interested in,’ he says, ‘or you may feel great enthusiasm but need time to explore slowly.’ Part of the purpose of education, in his view, is to help individuals discover the relationship between what they enjoy and what they do well—and to come to that understanding for themselves.

What has driven Prof Sargent’s lifelong commitment to learning, he explains, is something disarmingly simple: the pleasure of inquiry itself. ‘Having fun,’ as he puts it, lies in the daily act of asking questions and seeking understanding. It is this quiet, sustained enjoyment that carried a scholar once regarded as a slow learner to the highest levels of academic achievement. It also continues to animate him today, lending his presence an energy that reflects curiosity rather than age. His career traces a steady path defined not by haste or spectacle, but by persistent inquiry—gently affirming that aging does not begin with the passing of years, but with the moment one stops asking questions.

Profile of Prof Thomas Sargent

Prof Thomas J. Sargent is an American economist and a leading figure in modern macroeconomics. He is best known for his influential work in macroeconomics, monetary economics, and time‑series analysis. Together with Robert Lucas Jr., he helped lead the ‘rational expectations revolution’, which fundamentally reshaped the way modern economics is analysed. Prof Sargent received the 2011 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering contributions to empirical research on cause‑and‑effect relationships in the macroeconomy. In the later stages of his career, his research has focused on heterogeneous agent models, which examine how economic fluctuations affect different income groups and highlight the close link between macroeconomic policy and wealth distribution.

Chinese Text: U Wai Ip

Chinese Editor: Gigi Fan

English Translation: Bess Che

Photo: Jack Ho

Video: David Tong, Sam Chan & UM Reporter DT Hong

Source: My UM Issue 150